A robust water contingency plan is crucial for any animal research facility, helping protect animals and research integrity during emergencies. In our first article from this series, we outlined the critical components and implementation strategies for developing effective water contingency plans. In this second installment, we dive deeper into an essential aspect of these plans: identifying the specific types of water your facility should store, along with practical methods for storage and distribution. Selecting the appropriate water resources and storage solutions ensures your facility is fully prepared to maintain animal welfare and sustain research activities during unexpected water supply disruptions.

Types of Water to Store and Storage Methods

Potable (Drinking) Water

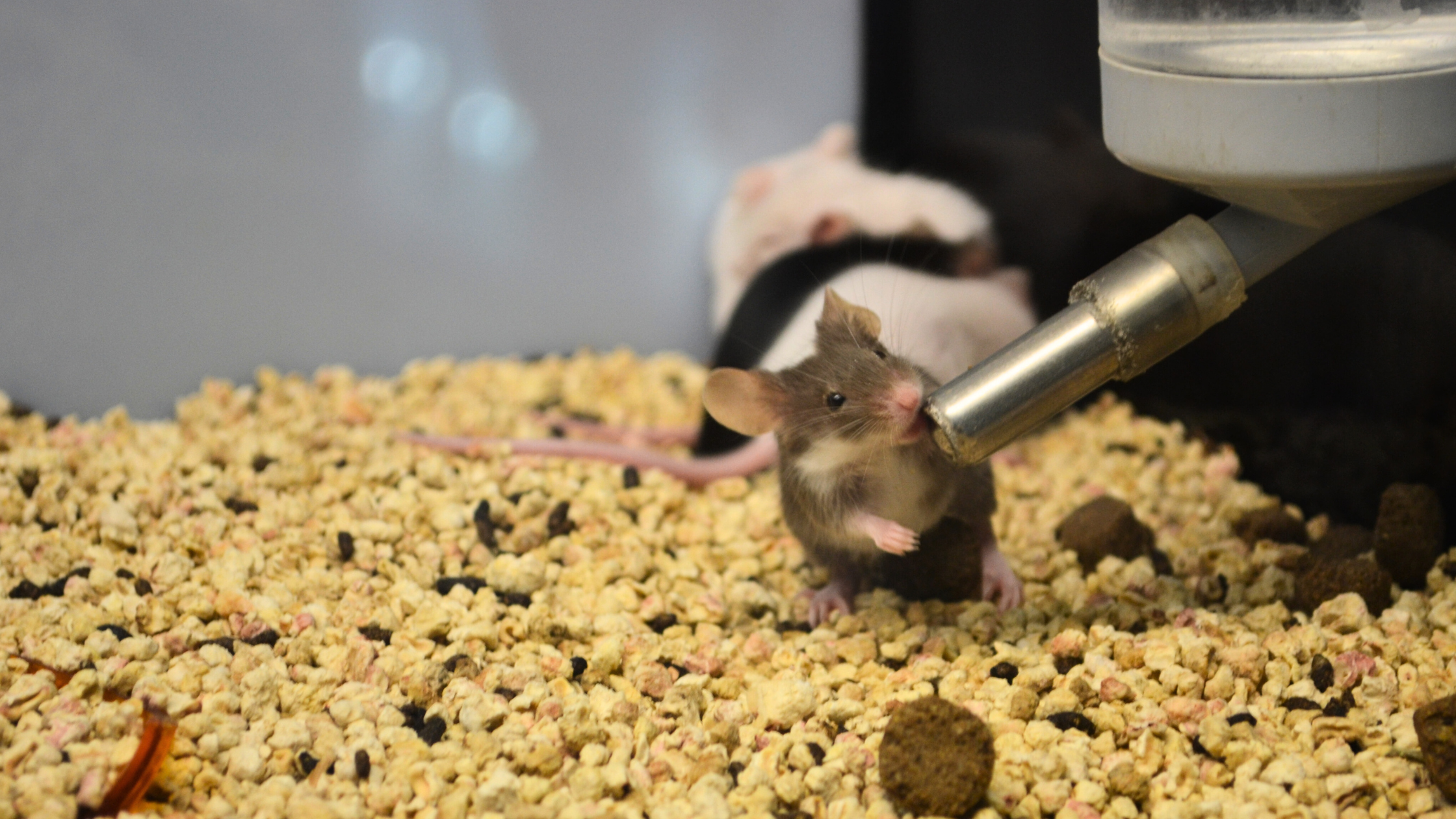

The primary type to store is potable water safe for animal consumption. In most facilities, this is plain drinking-quality water (tap or filtered) that the animals are accustomed to. Potable water is used for nearly all species’ daily drinking needs, so having an emergency supply is crucial¹. Stored potable water can be in the form of sealed water bottles (e.g. gallon jugs or smaller bottles) or large containers. Many facilities keep packs of bottled water on hand for emergencies, as these are ready-to-use and have a long shelf life if properly stored.

Treated or Purified Water

Some research animals receive specially treated water (such as reverse-osmosis (RO) purified water, deionized water, or acidified water) as part of normal husbandry to eliminate contaminants or pathogens. If your facility normally uses such water, the contingency plan should address how to provide it during an outage. This may involve storing some purified water in advance or having a way to treat stored water. For example, one vivarium reliant on an RO system for drinking water noted that if the system failed, bottled drinking water would be used as an alternative supply². In practice, short-term use of bottled or tap water is usually acceptable to keep animals hydrated.

Sterile Water

Facilities with immunocompromised animals or neonates might require sterile or autoclaved water. If animals normally get autoclaved water (to eliminate microbes), the plan should account for outages of the autoclave or water sterilizer. One approach is to keep a reserve of sterile water (in sealed containers) or the means to rapidly sterilize water if needed. For instance, a contingency plan might state that if water quality is in doubt or potentially contaminated, it will be autoclaved (boiled) before use, provided power is available³. If the equipment for sterilization is down for an extended period, the plan may allow switching to unsterilized potable water or commercially bottled water as a stopgap⁴. Always consult the attending veterinarian to weigh the risks, short-term use of clean tap water may be preferable to dehydration.

Aquatic Systems Water

If the facility houses aquatic research animals (e.g. fish or amphibians), they have large-volume water needs and life-support systems (tanks, filters, aerators). Stored fresh water for aquatic tanks may be necessary if an emergency interrupts the normal water supply or if water quality drops. Some facilities keep large drums of dechlorinated water for fish systems. Additionally, contingency procedures might involve partial water changes and portable aeration. For example, one plan specifies that during a power outage (affecting filters/aeration) longer than 24 hours, 20% of water in each fish tank should be manually replaced with fresh water daily to maintain oxygen levels³. Including instructions for aquatics (and having battery-powered air pumps or oxygen sources) is important if applicable.

Storage Methods

Choose storage methods that keep water clean and accessible:

- Sealed Containers: Large food-grade water barrels (e.g. 50–55 gallon drums) or jerry cans can store bulk water. Ensure they are kept sealed to prevent contamination, and label them with fill dates. If using large drums, the plan should have a means to dispense the water (hand pumps, spigots).

- Bottled Water: Individual bottles (1-5 gallon containers or even cases of personal-size bottles) are convenient and sanitary. These can be distributed quickly to rooms. Bottled water is ready to use – for instance, staff can pour it into animal water bottles or water bowls as needed. One university plan indicates that in a water outage, bottled water can be purchased from local stores to supplement the supply³.

- Water Pouches: Some rodent facilities use bagged water pouches with drinking valves that attach to cages. Pre-filled pouches like AquaPak® are sterile and have long shelf lives. They take up minimal space and allow easy installation on cages. However, they require compatible valves like AquaValve® on the cages. If your facility uses an automated watering system or water bottles, stocking some pre-filled pouches for emergencies may be worthwhile.

- Water Gel: HydroGel® is a popular solution for animal hydration during emergencies. Gel products are shelf-stable and can hydrate animals for several days. They also avoid the need for bottles or bowls in each cage. Many facilities keep a stock of hydration gel as part of their disaster kit.⁵

- On-site Water Tanks: Some larger facilities may have built-in emergency water storage (e.g. a cistern or rooftop tank) to supply the building’s plumbing for a short period. If such infrastructure exists, the plan should explain how long that tank can supply water and any manual steps to activate it. Also, the water quality in these tanks should be monitored or treated as needed.

Regardless of method, protect stored water from contamination and spoilage. Keep containers in a cool, dark area if possible, off the ground, and closed. It’s wise to rotate or refresh stored water on a schedule (e.g. quarterly or annually) to ensure freshness.⁵

Recommended Duration of Water Supply Storage

How much water should you store? The recommendation varies, but generally prepare for at least several days of independent water supply. A common guideline is to have a minimum of 3 days (72 hours) of water on hand for all animals (and staff) in the facility. For example, one set of animal facility guidelines suggests storing 1 gallon of drinking water per person per day, for 3 days (for staff needs)⁵ and similarly to have several days’ worth for the animals. This 3-day minimum aligns with general emergency preparedness recommendations for humans and provides a buffer for short disruptions.

However, many research institutions plan for longer periods to be safe. Some vivariums maintain at least a 5-7 day supply of food and water on site. For instance, Michigan Technological University’s contingency plan requires “a minimum of 1 week’s supply of food and water for the animals” to be kept in stock⁴. This one-week supply can be crucial in scenarios where disasters cause prolonged infrastructure damage or delays in aid. Consider the local risk profile: facilities in hurricane zones, earthquake-prone areas, or remote locations might opt for 1-2 weeks of water reserves, whereas those in urban settings might find 3-5 days sufficient with the expectation of quicker recovery or external support.

In determining quantity, calculate the daily water consumption for all your animals:

- Rodents: Mice and rats drink relatively small amounts (a few milliliters per day each), but if you have thousands of cages, this totals to many liters per day. Also account for water that might be needed for cleaning or misting if relevant.

- Large animals (dogs, primates, pigs): They consume much more water per day and may also require water for sanitation (e.g., cleaning bowls).

- Aquatic species: They might not “consume” water in the same way, but maintaining water quality might mean partial water replacements as noted earlier, which can use dozens or hundreds of gallons.

Ensure your stored volume covers the needs of all species in the facility for the target duration. It’s better to over-estimate a bit; an emergency could also halt your cage wash or autoclave, meaning you might need extra water for manual cleaning or to humidify areas.

Finally, remember to also store water for staff who may be on-site caring for animals during a disaster (usually 1 gallon per person per day). A holistic plan covers both animal and human needs.

Conclusion

Emergency water supply planning is not a one-size-fits-all exercise. Different species, housing systems, and research protocols demand different solutions. By thoughtfully selecting the appropriate water types and storage methods, animal research facilities can uphold animal welfare standards and maintain uninterrupted research during water supply disruptions.

Whether it’s bottled, gel-based, sterile, or purified water, the key is preparation. Incorporating commercially sterile, ready-to-use solutions like HydroGel® or AquaPak® can offer valuable peace of mind and operational efficiency in a crisis. As always, contingency planning should be revisited regularly and aligned with institutional protocols and veterinary guidance to ensure the well-being of both animals and staff.

Sources

- The University of Mississippi - Emergency and Disaster Plan for Animal Facilities

- Disaster Plan for Animal Care and Use at the St. Cloud State University Vivarium

- University of Wisconsin - Animal Care Emergency Preparedness and Contingency Plan

- Michigan Technological University - Animal Care Facility EmergencyResponse and Contingency Plan

- Oregon State University - Animal Facility Disaster Planning Guidelines

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.